Every once in awhile, I put away the current USPAP publication, my ASA newsletter, the Farm Equipment Official Guide, and Valuing Machinery & Equipment and pick up some light reading. My usual entertainment is a National Geographic magazine or a book of mid-1800s Western exploration, but when Craig Childs has a new book out, that’s always first on my list.

Every once in awhile, I put away the current USPAP publication, my ASA newsletter, the Farm Equipment Official Guide, and Valuing Machinery & Equipment and pick up some light reading. My usual entertainment is a National Geographic magazine or a book of mid-1800s Western exploration, but when Craig Childs has a new book out, that’s always first on my list.

In the mid 1960’s, when my father landed a job in the booming aerospace industry of Phoenix, AZ, we moved out from eastern Pennsylvania to the “Sonora Desert.” One thing I realized at a very young age is that the desert is far from deserted. Like the author who also grew up wandering around in the North Phoenix desert, I quickly came to learn that I was living atop the ancient ruins of the Hohokam civilization. It was common place to run into traces of that past civilization amongst the dumped washing machines and old bed frames in an arroyo. My memory of growing up in AZ was that around just about every turn there was a reminder that we weren’t the first to try to make a go of it here in the “arid zone.”

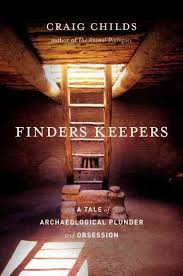

Craig Childs’ most recent book, Finders Keepers, A Tale of Archeological Plunder and Obsession, begins by discussing the substantial industry that has grown up around the antiquities trade in the American Southwest—and the tangle of legal and ethical issues that go hand in hand with this trade. Childs then turns outward from his home ground of the American Southwest, pointing out that the issues surrounding these artifacts are minor compared to the issues of Mesoamerica, Africa, Iraq, and the Greece and Italy … oh and then there is Asia.

Artifacts are, of course, removed from the plundered countries in many different ways. One clever little scam out of India involved taking advantage of reputable appraisers. The smugglers would commission replicas of authentic artifacts and then having the replica appraised as a fake. By attaching the appraisal (of the fake) to the authentic piece, they were able to easily get the authentic piece out of the country, through customs and into the western antiquities marketplace.

One of the main points that Childs makes is that despite all the legal and ethical finger pointing that comes with the global antiquities trade, there is no moral high ground. As Childs concludes, “We have no choice but to live among contradictions. If anyone tells you there is only one right answer to the conundrum of archeology, he is trying to sell you something.”

One conundrum involves repatriation. As native peoples demand that the museum artifacts taken from their lands be returned, they often learn too late that these items were treated with arsenic and other poisons to preserve them, unintentionally causing serious injury to tribal members who have handled the items.

Another difficulty is that of disrupted lives and communities as the U.S. government attempts to stop the illegal artifact smuggling. As federal agents have gone into small towns in the Four Corners area to enforce laws designed to protect antiquities, they have inadvertently left behind communities in shambles as the town’s only physician is hauled away in handcuffs and others key figures, overcome with public shame, have opted to commit suicide.

Questions gets even more complex when Childs focuses on the huge museum, academic, government, personal warehouses and even houses bulging at the seems with collections too large to fathom. He shows us that there are simply more antiquities in our possession than we as a society seem to be able to manage. So when something supposedly “belongs in a museum,” where in the museum does it belong given the abundance of other “priceless” items? I am reminded of the last scene in one of the Indiana Jones movies wherein Ark of the Covenant is moved to the basement of a huge anonymous government warehouse. Perhaps it is hopeful that— when the true provenance of certain pieces have come to light—major items in the Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York have been repatriated to countries of origin.

Mr. Childs closes his fine book with a final argument against archeological plunder: “At this point, considering all that has been removed, it is worth leaving the last pieces where they lie. As for what is already out of the ground, by all means, move it around, whether you repatriate it or pass it along to the next collector. … Let us appreciate what has been gathered and for the rest, let it lie.”

As you all know I am a Sacramento area machinery and equipment appraiser. Awhile back I was speaking with my friend Mandy Sabbadini ISA-AM, a Sacramento personal property appraiser who occasionally values Native American artifacts. I told Mandy that because I grew up in Arizona, I felt that I grew up around artifacts. She was surprised and asked why on earth did I not go into appraising them. Well, Mandy, I said, when I look at a John Deere 7330 tractor or a Multi Cam CNC router it is what it is and that’s pretty much it. When you look at an “artifact” how do you really know what it is?

After reading Mr. Childs’ recent book, I have even greater respect for my professional friends who appraise personal property and fine art. I’m also glad to stick to Sacramento area machinery and equipment appraisals.