Often in a fire loss case, the owner of the equipment cannot provide the basic building blocks of any equipment appraisal: what kind and quantity of equipment, manufacturer, model, age and condition. As mentioned in earlier articles, simply knowing that someone had 20 pickup trucks destroyed in a fire does not provide us with enough of the right kind of information to determine a value.

In hindsight, of course, a business owner would have an equipment appraisal done in conjunction with taking on an insurance policy and so would be able to use the report as a basis for the loss appraisal. We all know that best practices are not often followed; and of course this isn’t always feasible for businesses that have a moving inventory, such as the used auto parts yard that was the subject of one of our fire loss appraisals.

Best practices and due diligence aside, the fire loss equipment appraisal cases that come to us consistently lack adequate records regarding the lost equipment. And yet, equipment was lost, that equipment does have a value that needs to be paid to the claimant, and it’s our job to investigate, research and calculate that value. One of an equipment appraiser’s most important tools in ambiguous situations like this is the extraordinary assumption, as defined in Valuing Machinery & Equipment, 3d edition:

Extraordinary Assumption: An assumption, directly related to a specific assignment, as of the effective date of the assignment results, which, if found to be false, could alter the appraiser’s opinions or conclusions.

Primary Extraordinary Assumption

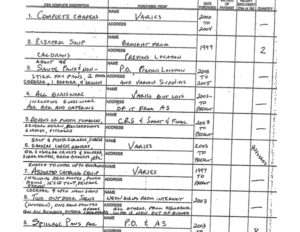

The first extraordinary assumption we make is that the assets actually existed & that they bear some resemblance to the asset list provided by the claimant. Often these asset lists are handwritten, with very few supporting details. They do, however, provide us with a starting point! In many of our fire loss reports, you’ll see a paragraph something like this one, just to clarify how little we know …

Descriptive information needed to accurately appraise many of the Subject Assets was not available; specifically, information regarding the make, model, size, capacity, quantities, meter readings and the appearance condition as of the effective dates is missing in many cases. In order to arrive at an opinion of value I have therefore made certain Extraordinary Assumptions about the description and the appearance condition of the Subject Assets listed in Appendix A based upon my estimate of what a typical subject for the given situation likely would be. (See Assumptions and Limiting Conditions later in this report for more information.)

This paragraph points to the next 2 extraordinary assumptions that help us provide a viable value for the lost equipment: descriptions and conditions.

Extraordinary Assumptions for Valuation

Given the situation, the location, the business itself, we make the best estimate we can regarding the description and and condition of the assets. Were the assets purchased new? Were any purchased used? How much wear & tear have they undergone? What do the maintenance records indicate? If any equipment survived the fire, what is its condition? How long has the equipment been in use and under what conditions?

Case Study: Restaurant Fire Loss

The same assumptions could be made for most fire loss situations. Most machine shops, for example, use their equipment in similar patterns, as do most food processing facilities or farming operations. All of these cases include using equipment and machinery in a process that is typical of the industry.

Where fire loss cases sometimes get more challenging is in the case of inventory. We’ll talk about some of those situations in another article.

Jack Young, ASA—MTS/ARM, CPA

Equipment Appraisal & Review for Fire Loss & Theft

NorCal Valuation Inc.