The Association of Certified Family Law Specialists published this article in their journal’s Summer 2021 ACFLS Family Law Specialist.

Appraisal review is, first and foremost, a standardized process that provides guidelines for assessing the overall quality of an appraisal relative to applicable standards, while concurrently addressing the degree to which that appraisal is credible, logical, and supported by evidence.

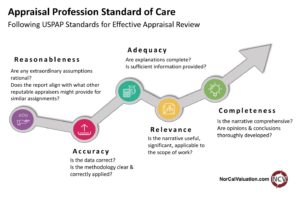

Credible appraisal reports are grounded in established professional standards and provide a logical presentation of evidence that supports an unbiased and defensible opinion of value. Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP), which sets the standard of care for the appraisal profession in the United States, defines a credible appraisal as one that meets criteria in the 5 areas of accuracy, reasonableness, relevance, adequacy and completeness. Other standards such as the AICPA Statement on Standards for Valuation Services (SSVS) for business valuation appraisals set similar criteria.

Review and expert rebuttal reports support a critical component of USPAP’s pervasive principle: to support public trust in the appraisal profession. Much like the accounting profession, the appraisal profession is largely self-regulating (real estate being the exception).

Appraisal review is part of how the appraisal profession conscientiously guides and regulates its members.

Why review is important

Any appraisal that disregards professional standards and fails to provide a logical presentation cannot be depended upon in a court of law or any contentious situation.

Attorneys cannot take for granted that any appraisal in a family law or buy/sell situation is worth the paper it’s printed on, and while a trained reviewer is often the best resource, any attorney can learn what red flags make an appraisal report suspect.

To help attorneys preview appraisal reports, this article provides a checklist of the most common appraisal report mistakes. In appraisal review courses, this list is thoroughly discussed using examples and best practices within the overall framework of how to properly review another appraiser’s work. Attorneys, however, find it handy in its own right as guidance to a superficial gauge of the credibility of an appraisal before calling for an appraisal review or expert rebuttal report.

How appraisal review can help your case

Typically, parties in a case involving valuation dispute will each get an appraisal and let the court figure out the details. A better option is to focus the case on the issues that matter most, using an appraisal review of the opposition’s appraisal report rather than a separate appraisal. You may also want an independent “opinion of value.” The following examples illustrate how review with an opinion of value can often be more useful than a review without an opinion:

A recent appraisal review with an opinion of value for a family law case identified five main points where the values concluded in the review disagreed with the work under review (WUR). The review report clearly explained the methodology and analysis that supported those conclusions. This information enabled the parties to focus the argument on the key points. In the end, only two of the five issues needed in-depth discussion in court. This is a typical outcome of a well-done appraisal review.

In another case, this one for an insurance loss dispute, the WUR had a number of failings as far as presentation and content. However, the opinion of value provided within the appraisal review indicated that value conclusion was spot on. This saved both sides a lot of time and fees so that they could move on to more challenging cases.

Is the opinion of value “correct”?

The question of requesting an opinion of value is worth consideration. Appraisal review can be completed with or without an opinion of value. This means that while the review will certainly indicate whether the report itself is credible and if the opinion of value stated in the original report is (or is not) properly supported, such indications do not necessarily indicate whether the value provided is “correct.” Remember, even a broken clock is right twice a day!

If you want the reviewer’s opinion about the value of the assets in the WUR, that information must be requested directly by asking for a review with an opinion of value.

In cases where the reviewer states that the opinion of value in the original report is not properly supported, and the review assignment includes providing an opinion of value, the reviewer will provide a properly supported opinion of value – either with an entirely separate appraisal report or by including the opinion of value within the review report. “Those items in the work under review that the reviewer concludes are credible can be extended to the reviewer’s development process on the basis of an extraordinary assumption,” per Comment to USPAP Standard 3 (c).[i]

Regarding review with an opinion of value, a second reviewer might even be asked to review such a review. This could be appropriate in especially complex or highly contentious cases.

Start by trusting your instincts

Early warnings of an appraisal’s credibility deficit often appear as a vaguely defined appraisal problem: the report fails to clearly and correctly describe the who, what, where, when, and why of the appraisal situation. USPAP requires that the appraisal report must be understandable to the intended user. In fact, the word “understand” appears in the recent USPAP manual over 300 times and almost always in connection with the Intended User — the who.

A reviewer friend of mine was watching surfers off Pillar Point in Northern California — home of the famous Mavericks International surf event — when a rather well-known tech mogul sat down beside him. They got to talking and when my friend said he was an appraiser the tech mogul’s eyes lit up. “I’ve got a problem,” he confessed. He’d recently received a business valuation report from a large international CPA firm – and couldn’t understand a word of it! What did his new appraiser acquaintance think he should do? Without hesitating, my friend — with the full force of USPAP behind him — suggested the mogul “call the firm, reject the report, and tell them that they need to prepare something that you can understand.”

If you are unable to understand or follow the analysis in an appraisal report, that’s a warning sign that a report may not be credible or defensible. Consider: If the report does not provide you or your client with enough information on how the appraiser arrived at the opinion of value, can you trust that opinion of value to be valid? Can you persuade someone else of its credibility? Can you expect a judge, jury, insurance company, bank, or other user to decipher and trust the report?

Confusion regarding the appraisal process and methodology is a clear signal that you need to work with an accredited appraisal review specialist. An accredited reviewer will analyze how competently the appraisal review addresses the appraisal problem and ascertain if the value is based on appropriate standards, evidence, research, logic, and reasonable assumptions.

What does appraisal review address?

Appraisal review generally addresses the complete report, but that’s not always necessary for every situation. Sometimes only a portion of an appraisal or just one important calculation is all that needs attention. The subject of an appraisal review can be narrow and specific or quite broad: as specific as checking a discount rate, verifying the analytical methods used to value one item, verifying market rents, confirming proper choice of index used, or checking adjustments made to one comp; or as broad as the entire report, the entire workfile, an inspection of the subject(s) of the work under review, or providing an opinion of value.

USPAP defines appraisal review quite broadly: “the act or process of developing an opinion about the quality of another appraiser’s work that was performed as part of an appraisal or appraisal review assignment; (adjective) of or pertaining to an opinion about the quality of another appraiser’s work that was performed as part of an appraisal or appraisal review assignment.” [ii]

USPAP further states that the subject of an appraisal review assignment may be “all or part of a report, workfile, or a combination of these” and adds that “Reviewers have broad flexibility and significant responsibility in determining the appropriate scope of work in an appraisal review assignment.” [iii]

What will you learn from a review?

Reviewers generally begin with analyzing the original appraisal’s scope of work, which should include the seven key elements of the appraisal problem: in lay terms, these are the who, what, where, when, and why. A reviewers will use appraisal jargon: the client, intended user, intended use, definition of value, relevant characteristics, effective date of value, and assignment conditions (including assumptions and hypothetical conditions). In some situations, effective date and assignment conditions can have great bearing on the report’s credibility. For example, in appraising damaged or destroyed assets for insurance loss claims, the effective date of value should be previous to the loss and all assumptions made regarding descriptions and conditions must be listed, documented, and explained.

The reviewer analyses how the report presents and examines how the report presents the four points of investigation necessary to solve the problem or the how: identification of subject property (what), inspection procedures, data researched, and appropriate analysis, which includes valuation methodology.

Is the appraisal complete, accurate, adequate, relevant, and reasonable?

The reviewer also analyzes each of the seven key appraisal elements and – when necessary for credible results – each of the points of investigation for the qualities of completeness, accuracy, adequacy, relevance, and reasonableness. A review report will not directly address appraiser competency. Instead, as appropriate, you’ll learn where and how the WUR lacks support, adequate explanation, includes inappropriate analysis or methodology, or fails other critical areas of concern.

These same elements can be used to review workpapers in cases where the reviewer is asked to review those records. Workpapers, although rarely submitted with an appraisal report, are a critical support for any appraisal. The USPAP Record Keeping Rule clearly states that work paper files need to contain “data, information, and documentation necessary to support the appraiser’s opinions and conclusions.”[iv] One family law case centered on a report that had vague discussion of the analytical procedures performed. A review of the workpapers revealed hardly a shred of evidence to support the value conclusion. In addition to the obvious problem of unsubstantiated values, the appraiser had failed to comply with the Record Keeping Rule, a requisite of the USPAP Ethics Rule.

What are the significant critical issues?

A review report will focus on the most significant issues — in light of the intended users’ requirements — rather than making a list of minor errors. Appraisal practice is largely about matching the right analytical procedures to assignment’s appraisal problem. Not surprisingly, the most significant issues addressed in appraisal review will often discuss whether the proper analytical procedures were performed and were performed properly. It’s worth noting that the word “analysis” is in the current USPAP document over 700 times. The reviewer has the duty to explain in an understandable manner what was not properly done in the WUR, what should have been done, and why it matters.

Distinguishing between significant issues and minor errors is an important aspect of the reviewer’s responsibility. While a preponderance of minor grammatical or calculations errors rightly disconcerts an attorney or an experienced appraiser, reviewers are concerned with the larger picture. Focusing on misspellings, for instance, when a report under review contains inadequate asset description that leads to market research errors, benefits neither the reviewer nor the intended user.

What are the reasons for disagreement?

The review report will discuss “reasons for disagreement” with issues identified. These reasons will be fully supported by a logical flow of facts, analysis and conclusions using an objective tone. Most, if not all, of the disagreements will be referenced to USPAP standards or other sources of appraisal standard of care.

A common error in family law cases concerns the specific definition of value required under California Family Law cases (In re Marriage of Cream).[v] An appraisal that depends upon any other definition of value — a surprisingly common error — can easily result in misleading appraisal results. For example, in a recent family case involving highly specialized custom-made equipment installed in a food processing facility, the WUR valued the subject assets based upon auction liquidation sales of similar items and did not consider the unique nature of the equipment, its higher cost compared to the similar item, its current use, shipping, and all installation costs needed to place the equipment into operation in a going concern enterprise. Although the analysis presented in the report may have be reasonable for the intended use of collateral lending, it clearly is not reasonable for a family law case. This inappropriate analysis resulted in greatly undervaluing the subject assets in the case.

In the end, reviewers classify issues uncovered in the areas of completeness, accuracy, adequacy, relevance, and reasonableness as they relate to USPAP and other relevant Standards. A useful review report will carefully avoid declarations regarding whether any of the issues at hand constitute a “violation” of USPAP; such determinations are the responsibility of a trier of fact, regulatory body, or some other entity with the authority to do so.

What about competency of the appraiser?

An appropriate review will avoid any discussion of the competency of the appraiser who provided the report under review. That is the Court’s job. Because USPAP provides guidelines for judging competency only by how the appraisal work is performed (and not the appraiser’s experience, knowledge, and training), appraisal review focuses directly on the appraisal itself, leaving any conclusions about an appraiser’s competency to the user of the appraisal review.

15 Most Common Appraisal Errors

These 15 most common appraisal errors are not ranked either by occurrence or severity and can be grouped into distinct categories:

Inadequate methodology

You may feel confused or frustrated if the report is vague and does not adequately explain the data or methodology used to reach a value conclusion or, as mentioned earlier, it seems to gloss over or ignore parts of the appraisal problem or analytical process. If the report fails to provide a clear understanding of why the assets are being valued in this way, the appraisal may suffer from these important methodology issues:

- Incorrect definition of value and/or relevant market

- No or inaccurate highest and best use analysis, also called current and alternative use

- Disregard of available market data with no explanation; i.e., cherry-picked market data

- Vague scope of work; failure to clearly identify the appraisal problem

Incomplete presentation

If you can’t follow how the appraiser reached the opinion of value, the report is incomplete. At the very least, the report should include enough analytical discussion to lead the intended user to the value conclusion. If at any point you feel like the report is not supported by evidence and is saying “just trust me,” that’s a good reason not to. What does an incomplete presentation look like? Here are a few clues:

- Conclusory with minimal analysis; leaping to conclusion without supporting evidence

- Failure to connect the value opinion with supporting evidence: Kumho Tire, ipsi dixit

- No support or explanation for adjustments

- Assumptions not listed

Misrepresentation of appraiser

Errors of misrepresentation are surprisingly common. Those of an appraiser claiming membership in an organization or compliance with USPAP are among the easiest to uncover. Does the appraiser’s CV include a USPAP class within the last two years? Does the organization list members on its website? Sometimes it can be revealing to make a phone call. In a family law case, an appraiser claimed a specific certification from a reputable appraisal organization. The organization, when contacted, clarified that the fellow had taken a class with them in the distant past but that, in fact, the certification he claimed did not exist in any form.

Appraiser objectivity is rightly assumed by users of appraisals and this assumed independence is a cornerstone of the public trust in the appraisal profession. The certification statement required by USPAP reassures users that this public trust is well-founded. Misrepresentation of appraiser objectivity can be as simple as entirely omitting, or not signing, the required certification statement.

- Claimed compliance with a standard such as USPAP when not compliant

- Exaggerated qualifications, including alleged membership in professionally recognized appraisal organization certification or accreditations

- Appraiser bias: i.e., value provided by seller, or dealer with who the client has had other transactions

- Lack of signed certification

General carelessness

Earlier we mentioned that an appraisal review does not nitpick at the expense of critical issues. Be aware of these distractions, however, because pervasive carelessness may indicate deeper problems in the development and analysis of the appraisal. Examples include:

- Errors in math, grammar, spelling, or punctuation

- Wrong location (Sacramento vs. West Sacramento)

- Careless use of boilerplate language that results in a report bloated with irrelevant and/or confusing content, including errors in dates and names

How to find a qualified reviewer

A qualified reviewer will be competent in the area of appraisal practice pertaining to the report to be reviewed. You probably know better than to hire a real estate appraiser to review a machinery and equipment appraisal, but what you may not realize is that the appraisal profession can be as finely divided as the legal profession.

The first sorting of appraisers is into three main property types: real, personal, and intangible. Real is real property, and while most attorneys are aware of the division between appraising residential and commercial properties, the differences don’t stop there. The residential real property appraiser who appraises urban properties in Downey CA may not be qualified to review an appraisal of a luxury oceanside home in Manhattan Beach; and commercial real property appraisers can specialize in urban strip malls, hospitality facilities, warehouses, or vineyard properties. The same is true for personal property appraisers, who tend to specialize not just in areas such as gems & jewelry, art & collectables, or machinery & equipment, but in even finer distinctions, such as art deco jewelry, early Japanese art, French antique furniture, construction equipment, medical & dental equipment, aircraft, or marine vessels. Within the intangible property profession, appraisers may focus on valuing employee stock option plans or certain kinds of business.

It’s also important to realize that not every excellent appraiser is automatically an excellent reviewer. That’s why organizations such as The American Society of Appraisers (ASA) and the Appraisal Institute (AI) have dedicated review education and training. Appropriate accredited reviewers for your case can be found through the ASA listings of reviewers in all appraisal disciplines at the “find an appraiser” page. AI is a good resource for reviewers of real property appraisals.

Click here to access the attorney checklist for preliminary appraisal review as mentioned earlier in this article. No registration required!

Jack Young, ASA—MTS/ARM, CPA

Equipment Appraisal & Appraisal Review

NorCal Valuation Inc.

[i] 2020-2021 Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP), Appraisal Institute, p. 28

[ii] USPAP 2020-2021, p. 3

[iii] Id.

[iv] USPAP 2020-2021, p. 10

[v] JUSTIA US Law, In re Marriage of Cream (1993) https://law.justia.com/cases/california/court-of-appeal/4th/13/81.html